Maybe it is just a way of coping, but I separate the sometimes hurtful things they do from the earnest and talented young women I work with every day.

I make excuses for them. They are just obeying their leaders. They trust them. They don’t question them. But they have good intentions.

The real soul breakers, I tell myself, can only have come from anonymous central planning.

This stratagem is not working well when it comes to Leitha even though I know that she is not in the top circle of power. Maybe it is her body language. She does not even wear that cover-up smile.

Leitha heads the other arts center in the Caravansery, a converted barn near the bookstore. There they weave cloth on a loom and make tapestries, liturgical vestments and dance costumes. I am never in her household. But somehow she shows up at unexpected moments wherever I am.

After my first summer on the kitchen staff they put me in the agricultural household. It is called Pneuma. Because of the hours dictated by farm work, we have our own cook, me. But somehow Leitha is often presiding and reading at our meals.

Singers in long robes, holding lighted candles, wake us up in the middle of the night. I am in the top bunk. I sit up, too groggy to remember the sloping ceiling. I hit my forehead again. Now I am awake.

We dress and stumble down the road to the main hall for another prayer vigil. There is Leitha, in charge of things. I struggle to keep my eyes open. In just a few hours, at five o’clock, we must go and milk the cows. I am sure that Leitha planned this.

It is Christmas morning. Even though I am no longer a year school student I am told to join the new students in the hall. We are opening our Christmas presents. Everyone has letters and cards except me.

They distribute the gift packages. There is a large box for me. The girls are opening their gifts from home, laughing at the thick woolen undies and sharing their photos and their candy.

I open my box. Inside there is another box, gift wrapped. I unwrap and open it. Inside, there is nothing. It is a totally empty box without even a Christmas greeting in it. I stare at this empty box. I get what they are saying:

Nobody cares about you!

I hear a gasp. The girls try not to look at me. I am ruining their Christmas spirit. I put the top back on the box. I leave quietly. This one could only have come from central planning which I am beginning to associate with Leitha.

It is Lent. We are having a simple supper in the fields. I am enjoying the thick slice of freshly baked bread and the hunk of cheddar. I hold a ripe tomato in my hand. We picked that only minutes ago. The setting sun casts its last rays of gold across the fields. It is a perfect tomato. I take a big bite. It is delicious.

You do not have the right spirit! I look up and see Leitha glowering at me. You are taking too much pleasure in your food. It is against the penitential spirit of Lent. But whether it is Lent or not, you should always have something unpleasant at each meal.

I have an idea for a chicken dish which I could not try out when I was cooking in the main kitchen. There were five of us, and we cooked three meals a day, with strict deadlines, for up to one hundred and fifty people, plus special meals for special people upstairs.

Maria was in charge. Though she was good natured she did not allow for any experimenting. But now I am cooking for only a dozen or so, and it is my chance to try out my “smothered chicken.” The pieces are lightly breaded and fried in butter, seasoned and then very slowly cooked until you could cut them with a fork.

I expect my farm girls to gobble it all up. But when I see Leitha eat a large second helping I realize why I made that special effort today. What do I care what Leitha thinks anyway. It makes me uneasy.

Whatever household I am in, they often pull me out to conduct Mass or sing folk songs. They just need more conductors than they have, especially when there are many visiting priests.

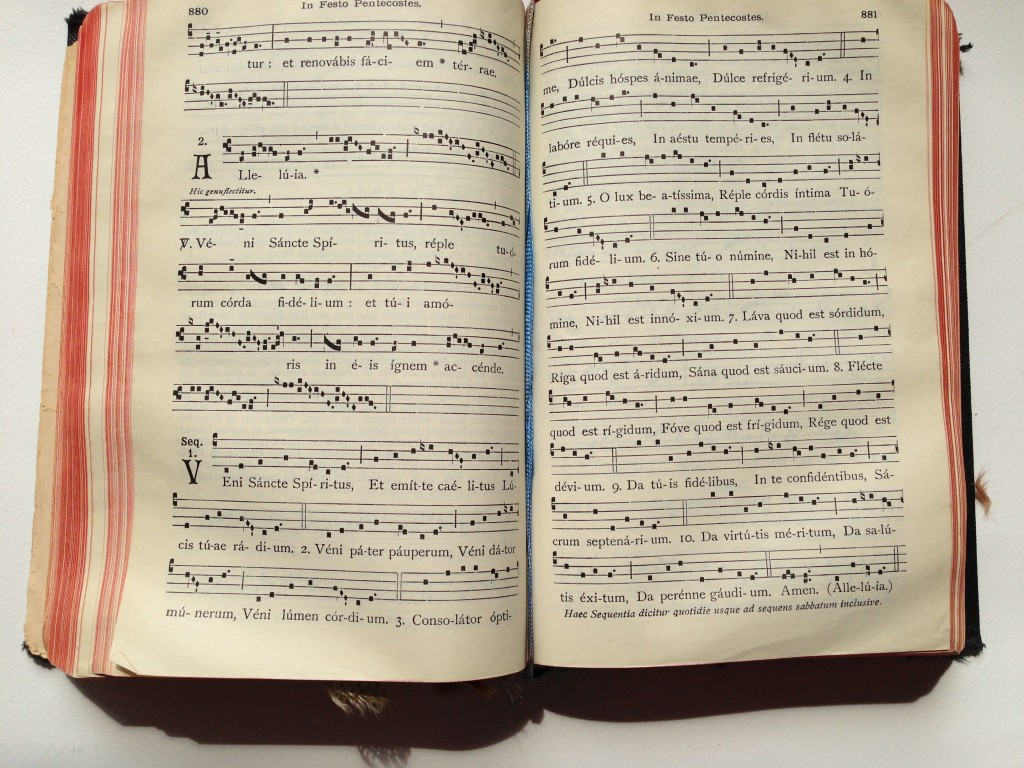

On Pentecost Sunday I conduct Mass in the parish church. The hymn Veni Sancte Spiritus (Come Holy Spirit) is sublime. Everyone loves it. However, it spans octaves. I know that.

I should have used my pitch pipe, but I have become so sure of myself that I never even carry it. I give the choir the pitch. As soon as we sing the first phrase I realize that I did not pitch it low enough. Disaster!

At the highest notes Rosemarie is the only one left who can squeak them out.

After Mass no one says anything. I know it is my fault – it is pure hubris, that’s all. Yet I am saying to myself, why didn’t Leitha stop me after I gave that too high pitch? She was standing right next to me, and she has sung this for ages. She wanted to see me fail.

That’s when I realize with a shock that something is happening to me that I hate. I am blaming someone else.

It gets worse.

We are required to go to a lecture that Leitha is giving. It is a special lecture on clothes and woman. We are not allowed to take notes.

Leitha comes to the podium dressed in a suit and a man’s tie. I cannot believe the nonsense she says about her subject. Hasn’t she ever felt the pleasure of wearing pretty dresses and hats and walking around in her mother’s heels?

I should try to understand her. Instead I think, no wonder she doesn’t want us to take notes. She suspects her lecture is total rubbish yet she wants us to endure it.

I am back in the main kitchen for a second summer. Summer is our busiest season with crowds of visitors. It is a seven-day, all day job with breaks of only an hour or two each day.

Often I am still scrubbing pots so large I could fit into them, and measuring out breakfast coffee long after the lights go out in the other households. This Sunday, amazingly, I am given the whole day off until dinner.

After a festive breakfast with a full dining room, Leitha, who is presiding, says that she wants a volunteer, just one person, who would make the sacrifice of doing all the dishes.

No one volunteers right away. Leitha scans the room. Slowly, one and then two hands go up. She looks directly at me. I raise my hand. Doreen, she says.

I just knew she would pick me. Why am I doing this? With a sinking heart I see the dirty dishes pile up all over the counters of the washing-up kitchen as people stream out of the dining room.

Even when there is a large group pitching in, it takes considerable time to do all those dishes. There is no dishwasher. There is only one double sink. You scrape, you wash, you rinse, you dry, and you put away dishes for about a hundred and fifty diners. I am there for almost all the rest of my free time which I really needed.

I have a lot of time to think of what I am doing to myself. I see why I am doing this. I am saying YOU CAN’T BREAK ME.

But I volunteered.

Recent Comments