The guard greets my mom. We walk up broad steps to what could be a palace, and my mom says that we are here to visit my granduncle, Tio Jose. I have never heard of him. I have no idea that his garden is on the other side of the divided well in my grandmother’s house.

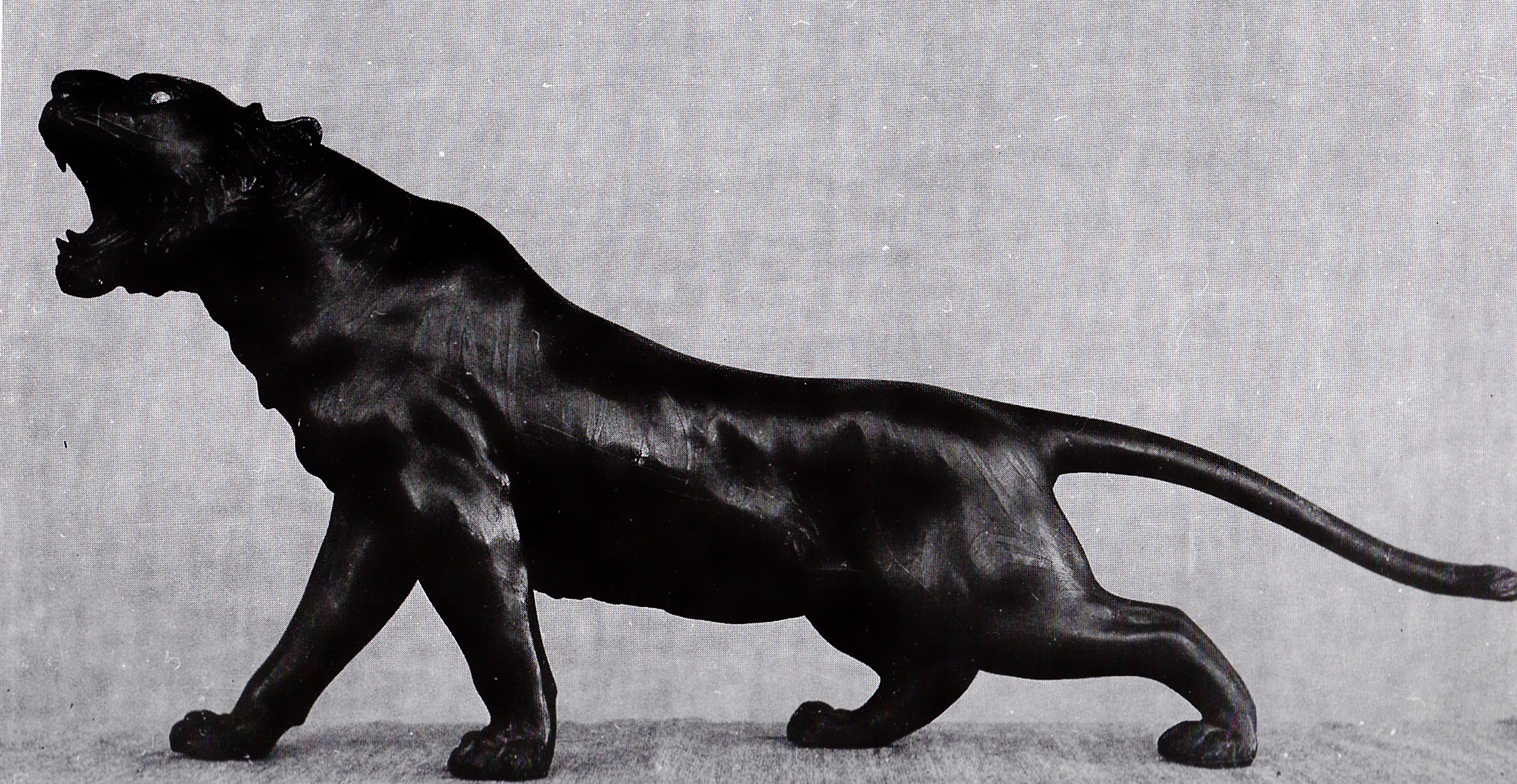

Tio Jose kisses my mom and me on both cheeks as all our relatives do. When my mom lets the amah refill her teacup, Tio Jose says come with me. He starts pointing out the beautiful things that are everywhere. He asks which I like. I like a little box with a lid. He nods. That is very fine, very old. Then he picks up another little box that is just as beautiful. The boxes have markings underneath to tell you who made what. All the rooms are filled with his beautiful things. I want to remember what he is saying. I understand that he thinks it’s important, even for a child like me, to know what he is saying. I see a tiger that’s not like the other things. It’s one of his beautiful things, but it’s fierce.

But my mom is saying goodbye. There is no talk of coming back soon, and my mom and Tio are saying goodbye as though it would be forever. Kisses on both cheeks, tight hugs. Tio Jose and his tiger disappear from my life.

Almost a lifetime later, I turn a page in a thick book that Tio Jose published about his Chinese art collection, and there is the tiger.

It’s a bronze. It has been with me all the time, the image of this tiger. Sometimes a tiger, sometimes morphed into a roaring lion, like the one in the bible who goes about the world seeking someone to devour. That day in my granduncle’s house my vague feelings of danger and sadness focused on that roaring tiger. Within a year, my mother died, my granduncle left Macau, and two years later, he died in Portugal. His enormous collection of Chinese art, which he loved to show to any visitor who asked, was scattered to the winds. It wasn’t just the art. It was their world.

Theirs was the story of old money in a changing world. It’s really the same old story. When you have more money than you need for generations, what do you do for your children? You try to teach them how to behave in paradise (on earth) so that they get to stay there. Good luck with that.

An optimist said, the world is so full of a number of things, I’m sure we should all be happy as kings.

Sure, but then there is that roaring tiger, both hunter and hunted. By now you’d think kings are an endangered species, but no, they’ve just morphed and multiplied: there is King Kong, Elvis, Hollywood royalty, tenured royalty, sports for kings, and there will be kings as long as there is a numero uno.

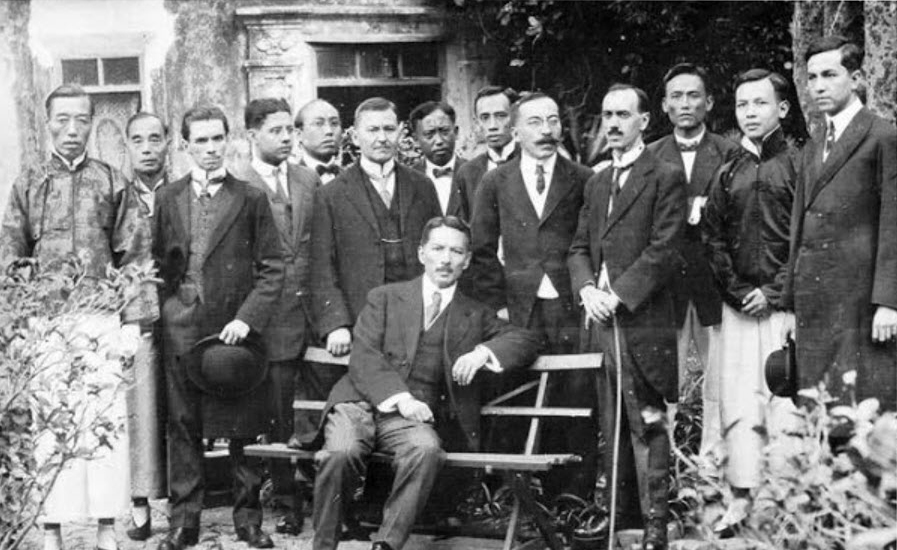

Jose Vicente Jorge and scholars and lovers of Chinese art and culture.

NOTES ABOUT CHINESE ART

by Jose Vicente Jorge

(translated by Doreen Jorge Cotton)

PREFACE

Disinterest is generally caused by lack of understanding. Allow me, then, to give some understanding of these Beautiful Things which, it seems to me, ought to belong to all those who care about matters of art.

It has been a long time since the Portuguese, though motivated merely by commercial interests, were touched, in their sensibilities, by the charm of Chinese art, and made Macau a center for the export of beautiful things from China, bringing marvelous ceramics to the furthermost European markets; and others borrowed, in this way, whatever was new and extraordinary in these works of art. This process marked, unquestionably, an epoch; and whereas interest decreased in Portugal, this did not happen in other countries, where in fact this style was stressed and without doubt is reflected in the arts of Europe.

The Orient, as is known, was always an inexhaustible fount of inspiration for Europe; at times, when it had tired of overused styles, it found in these distant regions a way to be different and strange and avidly took what it considered exotic and beautiful in the primitive arts. Thus we will find, in many eras and in many schools, a well-marked influence of the oriental arts in music, in painting, in sculpture, in dance, in theater, in ceramics, etc., etc.

And perhaps France is the country which, through its innovative tendencies, was readiest to receive the influence of distant arts and where the greatest number of oriental motifs were explored. The fondness with which it received the manifestations of Russian art was influenced certainly by whatever was new and unknown that reached that country, from near or far, which had on it a mark of the Orient.

Portugal, which was the first country to know the distant Orient, preferred to receive, sometimes, indirect influences, because our artists have shown absolute disinterest in all, or almost all, which is not all ready within the small limits of our continental territory, or in the dominant centers of European art.

Being limited in its field of operation, a national sentiment for art has not been readily conserved.

One of the interesting projects of the New State has been the promotion of artistic and literary works of its colonies; and mindful that Macau is a Portuguese colony for about 400 years, and as it does not have characteristics of its own but only those which have come from Chinese civilization, I feel obliged to add my modest understanding of Chinese art to help spark dormant interest.

I will not dwell long, but long enough to initiate studies of what I think is valuable.

This work is not a treatise about Chinese ceramics, as I would not venture so much.

These are simply notes, taken from various books, from conversations I have had with certain Chinese collectors, among whom were the viceroy of Chili, Tuan-Fang, the minister Yuan-Shi-K’ai, who later became the president of the Chinese republic, the foreign ministers Liang-Tun-Ien, Na-T’ung, Lien Fang and Kuo-Chia-Chi, and the governor of Canton, Chan-Chec-U, with all of whom I have spoken, and was able to observe, during the long period of 50 years when I made this collection. In the course of my official functions, I have had occasion to visit the palaces of princes and viceroys, the Imperial Palace, the museums of the emperor and the empress, where I marveled at the treasures that I saw, as much of ceramics as of other arts, all of undisputed and absolute authenticity.

I believe that when one has succeeded in overcoming the difficulties which Chinese ceramics present and can understand the motifs used in decoration, one will find a subject so absorbing and interesting that one will need no other stimulus to deepen one’s knowledge.

If my modest work serves to help someone, in however small a way, I would be gratified for my labor, for I would not have written in vain.

Macau, September, 1940

Jose Vicente Jorge

MY COLLECTION

I have about 10,000 pieces, representing the principal branches of Chinese art – ceramics, bronze, jade, painting, calligraphy, sculpture, engraving, enamel, lacquer, embroidery and furniture.

A reproduction of all the pieces would make this work very expensive and this book overly voluminous.

The pictures which follow are of the principal pieces and give a good idea of the collection, which when all is said, took me about 50 years to build.

I also found it of interest to reproduce some views of groupings, so that one can judge their decorative value.

Macau, September, 1940

Jose Vicente Jorge

My granduncle Jose’s family

Recent Comments